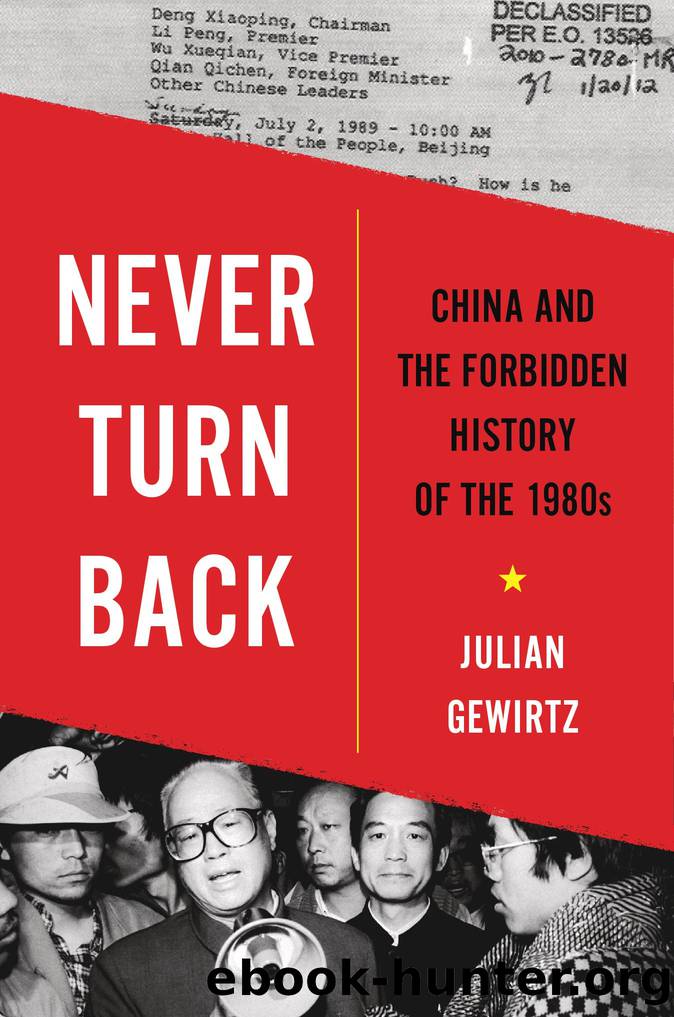

Never Turn Back by Julian Gewirtz

Author:Julian Gewirtz

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Harvard University Press

The year 1989 was laden with historical import from the start: it would mark the fortieth anniversary of the Peopleâs Republic of Chinaâs (PRCâs) founding in 1949, the seventieth anniversary of the May Fourth Movement in 1919, and even the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution. These seemingly unrelated anniversaries âhave a common theme,â Su Shaozhi wrote in January, ânamely, denouncing feudal despotism and carrying forward the spirit of democracy and science.â Su marveled at the fact that China, the Soviet Union, and many countries in Eastern Europe had all launched reforms of both the economic and political systems. âModernization is by no means merely economic modernization, or âFour Modernizations,â â he wrote. âIt should be political modernization and the modernization of people.â16

At the start of the fateful last year of the 1980s, Su gave voice to the central question of Chinaâs 1980s: What constituted modernization? His answer was a holistic transformation, from the systemic to the personal, encompassing not only the material realm of economic and technological development but also politics, âdemocracy,â and the individual spirit. Su held out hope that this vision of modernization could be realized within Chinaâs âsocialist system,â so long as it was profoundly reformed.

Activist and physicist Fang Lizhi had a more extreme judgment. âForty years of socialism have left people despondent,â he asserted. Fang saw a system that could not even correctly implement the âformulaâ of âpolitical dictatorship plus free economyâ because âits ideology is fundamentally antithetical to the kind of private property rights that a free economy requires.â However, he perceived a rising tide of democratization in society, largely driven by anger with corruption: âThere can be no denying that the trend toward democracy is set.â17 Fang submitted a letter to the leadership in January calling for the release of Wei Jingsheng and other political prisoners, which was followed by several open letters from groups of scholarsâone calling for âgenuine implementation of political structural reformâ written by Xu Liangying, and another calling for general amnesty for all political prisoners.18

Discussion groups on political reform, known as democracy salons, bloomed in bookstores and on university campuses across the country. Su Shaozhi, Fang Lizhi, and several other intellectuals organized a New Enlightenment Salon at Dule Bookstore in Beijing, while a charismatic student named Wang Dan organized salons at Peking University, describing his mission as pursuing âfull freedom of speech and academic freedom.â Wang said that Peking University âshould serve as a special zone for promoting the democratization of politics,â a parallel to the special economic zonesâ focus on political reform.19 Cultural activity also continued unabated. In February 1989, a sprawling exhibition of several hundred artworks, titled âChina / Avant-Garde,â opened at the National Art Museum in Beijing to celebrate the experimental art that had been created in the PRC in the 1980s. Posters advertising the exhibition showed a U-turn arrow crossed out, as if to say, âThere is no turning back.â The exhibition was closed down a mere two hours after opening, when artist Xiao Lu fired a gun into her installation Dialogue.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Arms Control | Diplomacy |

| Security | Trades & Tariffs |

| Treaties | African |

| Asian | Australian & Oceanian |

| Canadian | Caribbean & Latin American |

| European | Middle Eastern |

| Russian & Former Soviet Union |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19088)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12190)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8910)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6887)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6280)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5802)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5754)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5507)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5446)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5218)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5153)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5088)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4964)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4925)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4789)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4753)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4719)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4511)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)